Real-time Ecology

If you stand in a wilderness park and you look out across the landscape, you are looking at unknown territory. We don’t know what’s out there. Rangers may roam and field technicians may catalog, but they’ve only been able to view their own park through a pinhole.

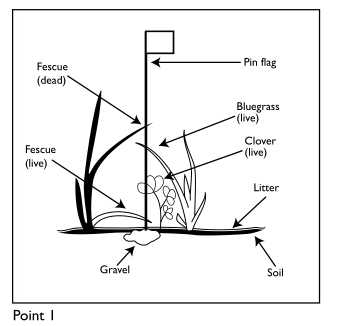

All our understanding comes from plots, samples, trackers, and observations. Here’s a plot:

Count every blade of grass, alive or dead in a tiny area. Identify every species in a 50m circle. Record soil 150 times. 3 person teams can do 6 plots a week for less than half a year before everything either dries up or freezes. Then they do it again 2 years later. In 10 years you might be able to see some ecological movement.

From this tiny pinpoint of information, we do our best to draw conclusions about the entire region, averaging those 120 sites to encompass 1,500 square miles of southern Idaho, or Nevada, or Oregon. We won’t even go back to see how things change throughout the year - we can only afford to visit once every other year.

What I just described is no small progress. It is cutting-edge effort. We only just started collecting information in a systematic fashion, trying to put the natural landscape under the lens of the scientific method. One of the main goals of inventory monitoring is to find out what is out there so we can notice when things change. It’s basic, but crucial stuff.

But now, we’ll be able to see the environment unfolding before our eyes. Satellite imagery has many flaws1 but it has powerful upsides. We don’t have to squint and intuit any more, the USGS can now track habitat shifts in real-time.

It’s not forests versus prairie, they can track the spread of individual species. A model matches what it can see of the plot - the satellite imagery - with exactly what was there - our painstakingly gathered plot measurements. Once it knows what a species looks like, it can recognize them across the rest of the country. The same plots I was tromping around on in 2017 are now teaching a model to recognize species from orbit.

This isn’t just interesting for tracking species,2 it’s a revelation to see the land for what it is. With information on what is really out there, right now, we can watch how every type of mouse, squirrel, and jay reacts to every type of grass, shrub, and tree as the landscape shifts. Being able to assemble the ecosystem puzzle is closer than it’s ever been before. We’ve barely begun to scratch the surface of so many things.

Things are going to get REAL busy. Gathering on-the-ground data to train the models, implementing new sensors to detect more environmental characteristics, tracking animal movements, checking the credibility of models, and modeling more more more interactions. There will be so much more TO do, now that there is so much more that we CAN do.