The "Species" Problem that Breaks the Endangered Species Act

Outline

The Endangered Species Act is the USA’s most important piece of environmental legislation. Far from being only about endangered species, it is the main method by which the nation prevents environmental destruction and protects ecosystems. Unfortunately the law depends on a clean definition for species, which doesn’t actually exist in nature.

Transitioning to a phylogenetic system would solve the errors that are coming from relying on an antiquated system of species concepts. (If you want the real write up, ignore me: go here.)

The “Species” Problem

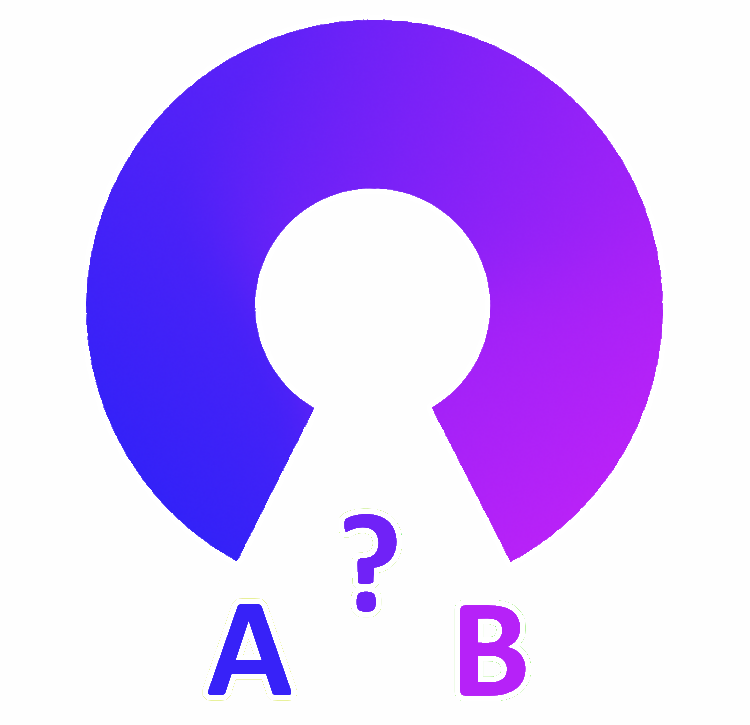

To explain the fundamental issue: In a smooth transition there is no perfect division point.

Where does blue stop and purple begin?

Where does blue stop and purple begin?

This is why attempting to draw a line between two closely related species is a never-ending battle.

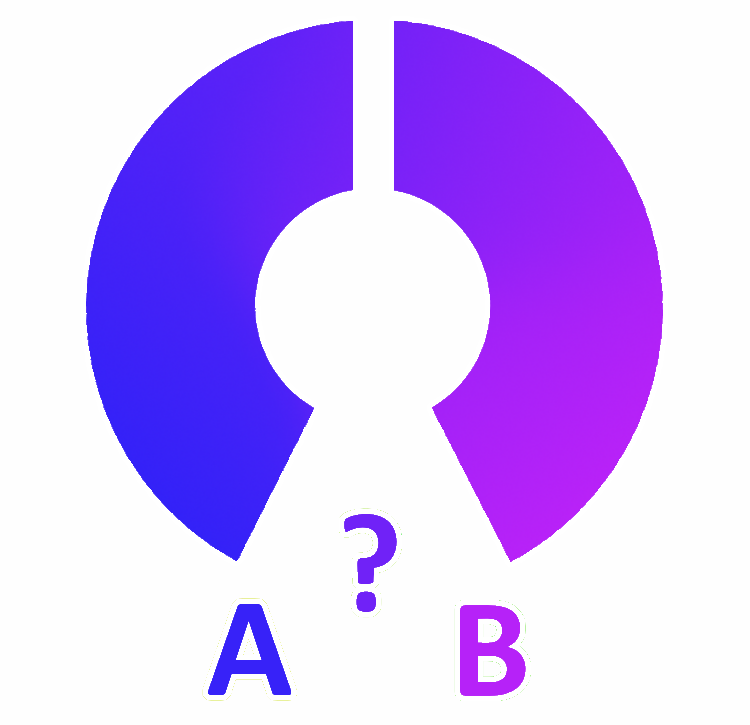

| A Ring Species | Two Species | A Split Ring Species |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Sometimes you have a smooth transition between a species and another such that they can breed with their neighbors, but not with the tail ends of the range. This is called a ring species. At first, this looks like one species that had some quirks at the far end. But if you remove some of the middle guys, it’s now two completely separate species.

It doesn’t seem like the existence of a couple individuals should define the specieshood of their relatives. The rest of the species didn’t change at all! You only removed a few linking individuals.

This is not a hypothetical - take the Polar Bear.

| Grizzly Bear | Species Distribution | Polar Bear |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Size, muzzle, coloration, diet, range, and niche are all different between these bear subspecies. They hybridize in the middle. Originally they were considered two separate species due to their differences, but they are now beginning to merge together.

But the alternative to defining a species by the existence of “linking individuals” in a gradient isn’t much better: Instead a species would be defined by whatever weirdos that don’t interbreed successfully. Where “species” begin and end would then overlap with dozens of other “species” defined by other partially breeding individuals in this paradigm. Once again, individuals have their specieshood defined by their relatives. So the problem hasn’t been solved at all.

Again, this isn’t a hypothetical problem. This species of deer was only discovered because dna tests showed they couldn’t possibly interbreed with other brockets.

Mazama americana, Red Brocket, has duplicated chromosomes ranging between 42 and 52. Therefore it cannot interbreed with other Mazama species. It was not discovered as a separate species until genetic testing, and could potentially be physically identical to other brockets. They are at least very difficult to visibly differentiate.

It gets even worse once we begin asking what we mean by “can’t interbreed.”

What if they choose not to interbreed, but could if they had to? Choice seems like a bad way to define a species.

But is it then defined by potentiality rather than actuality? Do we run around test-inseminating every subspecies with every other to see if it is viable? What about species which can technically breed but never do in the wild? Are they now a single species?

Does the existence of a Yakalo imply bison and yaks are the same species?

- Okay, so that seems impractical, but the alternative is including geographic barriers as part of what determines a separate species. Does the act of carrying some individuals hundreds of miles away from their relatives create a separate species?

It is mess. A pedantic, interesting one, but a complete and utter mess. There is no such thing as a natural dividing point between one species and another.

Enter: The Endangered Species Act

This would all be just be bit of fun scientific trivia, if our entire system of conservation wasn’t based on the Endangered Species Act. Now, suddenly, it matters very much where you draw the line to determine a species and how endangered it is. And environmentalists desperately need a concept of species to cleanly exist in nature. A fun little paradox has turned into a vicious fight with enormous repercussions for national parks, species, cities, industries, and livelihoods. Commercial companies and state governments with millions of dollars and millions of jobs ride on the line.

Preventing extinction is extremely important. However, these problems turn into paradoxes in cases where subspecies are changing in front of our eyes. When endangered species are interbreeding until they are no longer a distinct group, do we intervene and stop them? Is this survival or extinction?

A Red Wolf which may soon disappear by merging with coyotes. To confuse matters, Red Wolves might be a hybrid between gray wolves and coyotes long ago.

What about when there are entire communities of semi-independent species called a “species complex” — do we expend every effort to save all of them? Treating a species complex as several completely independent endangered species would be unfairly devoting resources to its care, but it would also be unfair to treat a species complex as a mere single species.

Phylogenetic Definition

In the traditional species-level approach, many paradoxes occur that can be resolved with a phylogenetic understanding. “Phylogenetic Diversity” or “Evolutionary Distinctiveness” are methods that measure evolutionary distance. By adding up all the genetic differences between species, these metrics allow us the measure the similarity of two groups. The definition of “species” no longer hinges on whether individuals can (or will) breed, solving many of the above headaches. A phylogenetic lens is especially useful in the cases of subspecies and diverging species.

- Instead of either “species” or “not a species” divisions demanding an impossible answer, partial divergence is measured and reflected. 4 species can equal 8 partial species with this system.

- The split of a species into two “new species” does not suddenly require twice the species conservation effort. Instead effort would be split between these very similar species populations according to their uniqueness, as it should be.

- By the same token, partially diverging populations that have not yet graduated into being considered separate species have their importance recognized due to their genetic diversity.

- Lastly, the “extinction” of a species into the wider population via hybridization is reflected. It reduces concentration of diversity in a subset of the population, but adds diversity to the pool.

Phylogenetics allows us to seamlessly scales from individuals, to populations, to species, to genus - each group can be compared and valued for the diversity it contributes to the larger picture. Phylogenetics seems to be a lot closer to the way nature operates, and I think using it will help us make better decisions for how to protect the wild diversity that we love. No matter how those creatures decide to interbreed and whatever form they take.