Indigenous Relationships with Nature

First Nations and Conservation

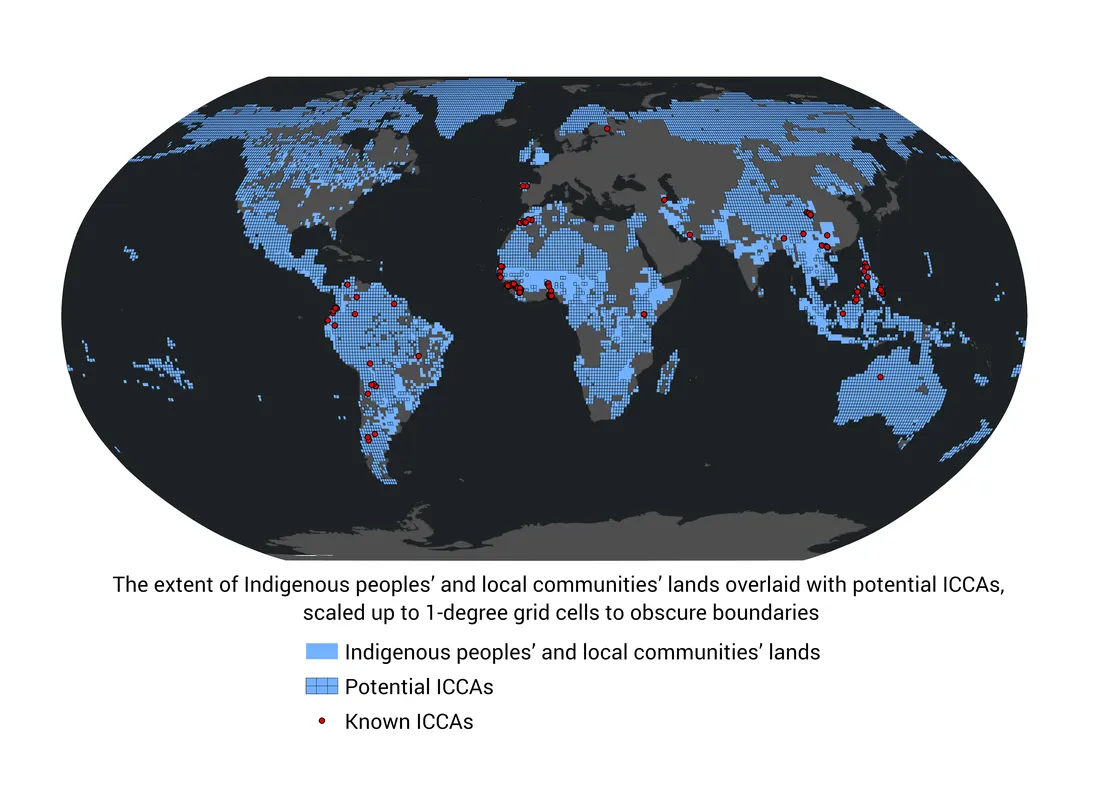

Native people have been intentionally shaping the land for centuries, and we are only recently realizing that they have cultivated vast areas into more bountiful landscapes for themselves. According to one paper 75-95% of the land area on the earth has been human-influenced, and many of those areas are considered the highest examples of “natural” and “pristine” - the opposite of degraded by human influence. Furthermore, First Nation’s make up 5% of the people, but manage 80% of biodiversity (also stated here).

Most of the remaining natural land is managed by indigenous people.

Indigenous people’s philosophy about what is right when it comes to land management is very different from the academic world.1

Reciprocal Relationships

The centermost difference I noticed in indigenous conservation management is that they are fundamentally in a relationship with nature. When they interact with nature, it is not as simple as documenting, harvesting, or restoring, but more of a “pact” or “bond” which they enter into with the land. This comes through in paper after paper on indigenous land management. A close second is the reciprocal aspect of that relationship. Looking for how to give to nature. A practical example is if you take something or trespass, you give something or ask forgiveness. Or you might practice many good deeds in the understanding that the landscape will be in a good relationship with you.

Some First Nations have such a strong relationship with landscapes that it is considered “kin” and destroying the land the same as self harm. For example, the Raramuri of Chihuahua call iwi the soul. Iwigara is the total interconnectedness we are within, participate in, and life in all its forms. Milpas is their word for optimal land use. Concretely this has resulted in continued to sustainably harvested grass despite the aridity and changing economic conditions. The Anishinaabe of the Great Lake’s Region echo this in their outcry that we are losing our relationship with water. They have the word inawendiwin for “relating,” which is core to the Inishaabe expertise/successful way of life. Likewise they view creation as a family and their place in it must be honored. They explicitly respect both individual and collective. They look on environmental “knowledge” not as understanding relationships but the actual relationships themselves.

Signs of respect at a sacred place.

Astounding accomplishments with indigenous land ethics can be observed. The first nations of India maintained a network of Sacred Groves for literaly thousands of years. “Up to 30 percent of land and water were fully protected as sacred sites. Certain valued resources such as Aquilaria, with its fragrant wood, or bamboo were harvested with great care.” The people of Hawaii managed to live in high density while sustainably managing the immense biodiversity of Hawaii. Their conservation practices were so finely controlled that routine practice was to catch birds, pluck a few feathers, and release them. Disobeying these rules would be met with harsh punishments.

But it is a mistake to think that traditional first nation’s management is simply “best.” It isn’t flawless. It isn’t a direct path to eden. In fact it is much more grounded and practical than it’s often depicted. In addition, indigenous land ethic is built for a person-level or tribe-level relationship to land rather than a city-scale or global-scale relationship to land. It doesn’t hold all the answers in our modern circumstances.

Megafauna Extinction

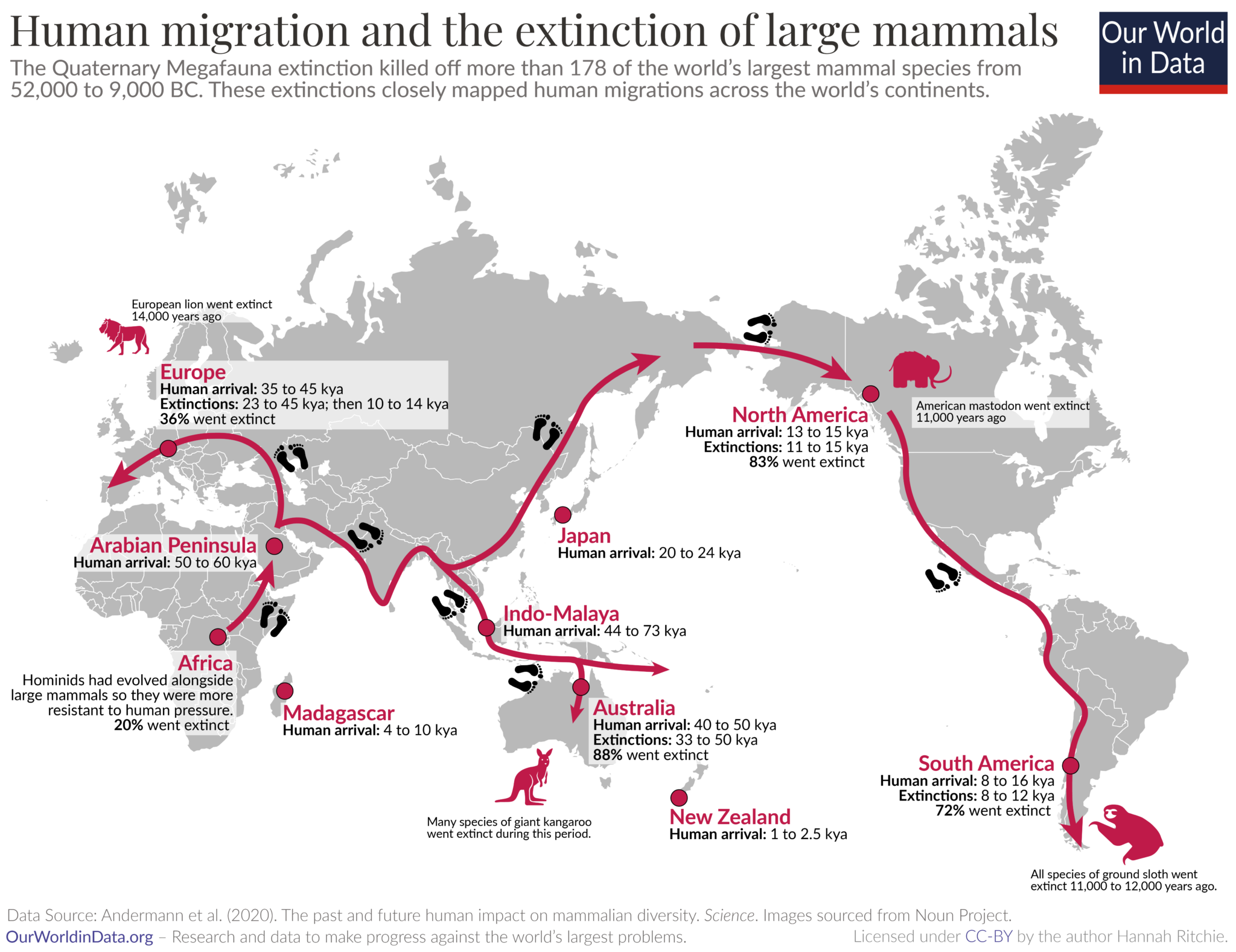

Indigenous land ethic is not enough to protect hundreds of species from extinction. The path of expansion by indigenous people (all humankind) is the same as the path of extinction of large carnivores and even large herbivores. While this was first noticed in North America, the pattern holds true across the entire world from Australia to Europe. (With one exception: Africa.)2 Even on Hawaii there were a wave of extinctions before the practices of sustainable co-existence were established.

When humans arrive, large animals go extinct.

This is an important fact - the wave of biodiversity loss is universal and significant extinctions began over ten thousand years ago which are continuing to have repurcussions on today’s ecosystems. Returning lands to the way they were 100, 500, 1,000 years ago is an exercise in arbitrariness.

In addition, the people who depended on the land for their livelihood and survival spent a great deal of time for purposes which no longer are valuable to us. For example in north america, they maintained clearings so they could see approaching animals, burn landscapes every two years so they could harvest better reeds, and increase oaklands for their acorns.

Natural Icons are Often Human Landscapes

Previous conservation ethics about “keeping lands people-free” were misinformed. These beautiful natural lands were not “people free.” The landscapes indigenous people created were widely regarded to be the most beautiful in the world, as in the painful case of Yosemite valley. Even the Sequoia redwoods of California might have persisted as a byproduct of human land management. 3 The more biodiverse portions of the Amazon seem to be intentionally caused by First Nation’s soil cultivation.

What they wanted to preserve versus what their management created.

These facts do not negate what indigenous people have to teach. Their traditions are much more longterm than the modern era’s short time horizon. If we want to recreate that, we should learn from them. If we want to interact with the land, especially the wider ecosystem’s movements, we should learn from them. If we want to recreate their biodiversity, we should learn from them.

The question at hand is: how do we conserve nature with our modern living standards, increased physical powers, increased awareness, decreased daily interaction, and changing priorities.

- I feel like I have to note that I don’t think Indigenous Ways of Knowing are superior to scientific approaches. They have different purposes. I do think they have a lot to contribute to one another. Native people are experts when it comes to living on and with the land. They know intimately how the land reacts to their actions, and are informed by knowledge that is both older and more of a mosaic than the scientific knowledge base. [return]

- The exception proves the rule: humans evolved into humans in Africa, and large mammals had the millions of years they needed to evolve successful life strategies “coexisting” (escaping) humans. [return]

- Redwoods apparently colonized California 20 million years ago, and at one point covered a large part of north america. They slowly became constricted and today only survive in a few scattered groves and the coast. Native american peoples arrived somewhere around 30,000 years ago. Their regular cultural burning seems to favor the survival of redwoods. [return]