Novel Ecology Literature

Outline

What is Nature, What Do We Do About It?

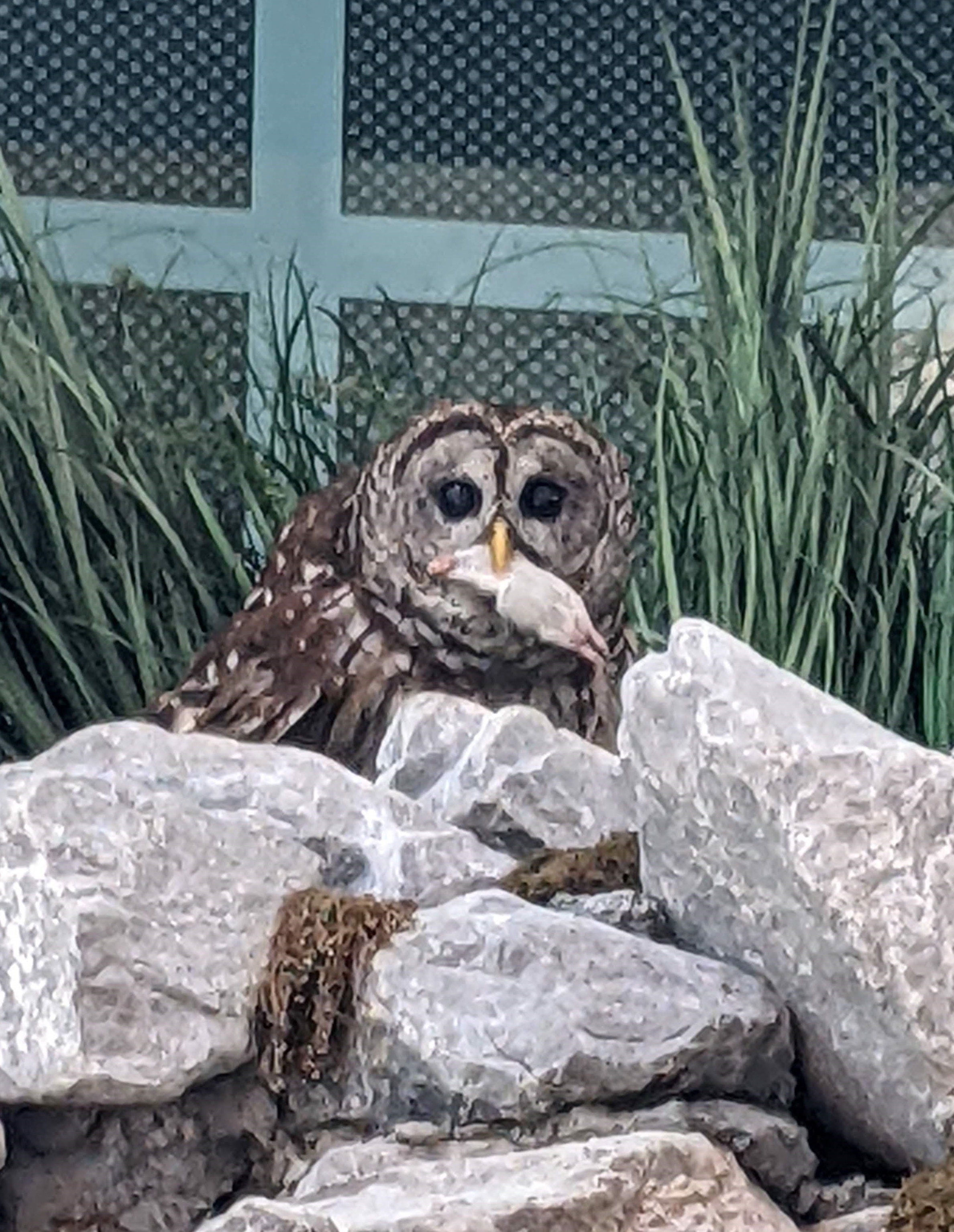

| There’s a lot of contradictions with the traditional concepts of ‘nature’ and the normal methods of stewardship. I’ve touched on some of them when I talked about GMO’s, the species problem, and when I tried to list all the goals of conservation. I thought they were simple problems that would resolve themselves after a little critical thinking. But now I am not so sure. I have found myself deep in a pit of uncertainty after digging deeper and deeper down the rabbit hole. So for those interested in confronting the foundation of their most cherished values, I have a few books to recommend: |  Gazing into the void, pondering his next move. |

Ghosts of Evolution: Nonsensical Fruit, Missing Partners, and Other Ecological Anachronisms

By Connie Barlow

The avocado no longer has an herbivore large enough to swallow the pit. It has been slowly falling down hillsides and into valleys, dying from lack of propagation ever since the giant ground sloths ceased to be (eons ago). The same is seen in the honey locust and the Kentucky coffeetree, both of which have giant pea-pods with peas the size of milkduds and hard as rocks. There are strange devil’s claw seeds, which are so giant that they seem to be intended to wrap around ankles to hitch a ride. Yet there are none large enough to carry it. There is a large desert gourd which lays on the ground and rots, instead of crunched by a massive beast. Perhaps the persimmon and the pawpaw have the same problem, with their giant seeds. Nature is not in balance, and never has been.

Specialization

Where mangoes grow, elephants swallow them whole, seed and all. Many fruit seeds have thick coats to resist being destroyed while being eaten. They are so specialized that they can no longer sprout unless they have been eroded by teeth and digestion. And there is body chemistry to consider: deer and other foregut digesters (browsers) can’t eat fruit because their stomach bacteria are in the “forefront” and fruit is too acidic. Hindgut herbivores (grazers) can handle the acidic tang of fruit, but the largest native left in North America is the beaver.

Outdated or Timescales Too Big to Imagine?

Each of these strange and wonderful plants are highly disadvantaged today because their clever adaptations have suddenly (thousands of years ago) become moot. More intriguingly, perhaps they can simply wait it out, until a new herbivore migrates or evolves back into their lives. It’s not just plants. The pronghorn antelope is one of the fastest animals on earth, ridiculously over-equipped to outrun its only predators: the wolf and mountain lion. It’s still shaped for 10,000 years ago, when the American Cheetah went extinct.

To Thrive Once More

To me, this is a wild picture of a very erratic and yet beautifully strange natural world. It seems wrong to consider nature on the short term with these complex life cycles unfolding. And it hints that humans might be able to do good by helping species tide over intervals. These species seem as if they could once again thrive if they made it to the other side. It suggests that there are interactions lying in wait to re-awaken, if we rearranged nature. Such interventions like humans keeping the Torrey pine, avocado, and the ginkgo alive, seem positive.

Ancient potential

Where do Camels Belong?: The Story and Science of Invasive Species

By Ken Thompson

Here is yet another example of large timescales. Nature moves and remixes itself a lot more than you thought. And nature is very keen to be “invasive” if it can. Species can travel thousands of miles on rafts, or wind to distant lands. Furthermore, official native species lists are suspiciously organized. Species which clearly escaped from cultivation 200 years ago get included as natives and staunchly defended against “new invaders.” Plentiful rabbits are “nonative” but the elusive brown hares are “native” despite being naturalized in the same ice age. The wild oat is categorized as invasive, despite presence for 3,000 years. The whole concept of “nativeness” is a thoroughly human imposition of moralizing about where species are permitted to exist. We should not be shy about nonnatives when it comes to what is “natural.”

Nonatives and Biodiversity

On the effect side, if you are worried about invasives driving out biodiversity: Non-native species most often increase biodiversity and form even more intricate thriving ecosystems. Non-native are found providing food and habitat for endangered natives, and assist in succession. Yet there is almost no research into these benefits. Removing invasives is often a cure worse than the disease. Eradication work causes soil compaction, releases other invasive species, inhibits native re-establishment, and generally fails to eradicate the invasive. Furthermore, natives are recognized to “act invasively” indicating it is not “belonging to a place” that is good.

Nonatives and Forever

Nature is dynamic, adaptive, ever shifting. Ecosystems never remain in place for long. Invasive species often fade away: second growth forests lack all the “terrible” invasives (honeysuckle, bindweed, multiflora rose), Argentine ants have collapsed against expectations, exotic grass Melinis is in decline, garlic mustard declines after 8 years. On the flip side of the coin, native species naturally experience sudden declines. Hemlock trees were nearly wiped out 5,000 years ago in a natural process, but seeing it happen again today is considered unnatural. Only 8,000 years ago the camel went extinct in North America. The great ancient redwoods, so iconic of California, are a mere 10,000 years recent. (and may be a product of human interference with natural ecosystems) Would bringing camels and cheetahs to North America be introducing them, or re-establishing natives? What timescale makes the most sense for natural processes, and does it even make sense to care about origin?

A rambunctious garden.

The New Wild: Why Invasive Species Will Be Nature’s Salvation

By Fred Pearce

Nature, in this book, is the process. Nature is powerful, adaptive, and capable. In this version, it is adaptation and survival that make nature so magnificent. Even the most inhospitable places are found to be quickly colonized and to thrive with biodiversity. Nature has spawned bacteria that eat plastic, insects that thrive in urban wastelands, species only found on toxic sites, and birds whose only habitat are urban landscapes. Keeping ecosystems stable, favoring weak species, fearing new species, and ignoring the biodiversity of polluted landscapes is wrong. Protecting Nature only suffocates it.

Nativeness:

On a brand new island formed in Iceland, carefully guarded from any human influence, many of the species were “unnatural” if native means natural. Plant species immediately migrated from Europe by riding the birds, and many of the insects did too. One of the keystone species, sea-sandwort, lives everywhere from Siberia to Ireland. Fighting invasive species is fighting a key natural process that allows nature to thrive.

Degraded Ecosystems:

In our polluted ruins, metal mines, and abandoned lots thrive some of the most biodiverse areas with some of the most rare species (biodiversity of insects). Human-made habitats are not antithetical to nature, but a new opportunity seized creatively and zealously.

Damaged Forever:

Any land abandoned by humans quickly returns to the business of flourishing. Famously the Chernobyl exclusion zone now hosts large wolf packs, and the demilitarization zone has become a world class wildlife refuge. Nature is powerful and robust given the opportunity.

Invasive Species:

Scientists struggle to find invasive species leading to extinctions, and most evidence comes from islands: places where entire ecosystems naturally return to non-existence as the island erodes away into the ocean. Most evidence is speculative, meanwhile non-native species contributing to biodiversity is rarely celebrated.

Extinction:

No qualm is given for the extinction of species, because extinctions are natural. Species rapidly evolve in response to change, forming entirely new approaches to life. Extinctions don’t even lower biodiversity, as other species quickly move in.

Hybridization, invasion, degraded ecosystems, extinction: All of these processes of nature (which we fight!) are ways in which nature thrives and overcomes obstacles. It is natural to invade, hybridize, regrow, and adapt to unnatural conditions. That IS nature: thriving wherever it gains a foothold. Yet we are disgusted by this “unnatural” situation, fear it will contaminate “real nature” and try to keep nature in a box, static, beautiful, and fake.

Urban wilderness, ripe for enterprising nature.

Strange Natures: Conservation in the Era of Synthetic Biology

By Kent H. Redford & William M. Adams

As I mentioned in my fragmentary post about GMO’s, we have touched the whole world, either through microplastics or through global climate. Soon we will touch everything with rippling genetic effects.

Humans have been changing the genome of species on earth ever since they walked the land. The alarm calls of birds, the spiciness of peppers, the buzz of rattlesnakes, the color of moths, or the heat tolerance of corals: all have been affected by our passing. Whether they evolved to defend against us or evolved to work with us; intentionally or not their genetics were modified by our presence. We have only become more deliberate with our influence. Cultivating, breeding, irradiating, and now editing shows how our precision has increased.

DNA is not Static:

The trouble begins with nature itself: Species regularly hybridize, DNA is transferred between species by viruses and bacteria frequently, and transposons jump between species too. Ticks move genes between cows, reptiles, bats, and elephants. I doubt these are mistakes. Its probably a key method of adaptation. For example, the gut bacteria as well as host/symbiont relationships have exceptionally high rates of horizontal gene transfer. The genetic code is hazy where it begins and ends. Its not just the DNA, its not just epigenetics, it interacts with the environment, conditions, and even other species.

Rescuing Species on the Verge of Extinction:

Species, if genetically bottlenecked, begin to fade from diseases, infertility, and inability to adapt. They have lost their rich landscape of genetics. Species can be rescued from slow inevitable slide into extinction by bringing in life-giving infusions of genes in a variety of ways: Allowing migration, allowing hybridization, involuntary migration, sterilization (of low genetic variety, or maladaptive genes), captive breeding, and artificial insemination. Once people are involved they can choose how deliberately manipulative to be. They can choose based on similarity, disimilarity, adaptive potential, specific adaptations, even specific genes. This is called genetic rescue, adaptive introgression, assisted migration, assisted adaptation, and assisted evolution.

Guided Evolution:

Once you are targeting successful species, you are guiding evolution. Not letting species go extinct immediately lets the cat out of the bag. And once you are specifically targeting genes, how you got the gene might not be that important. It could be already in the population, it could be rapidly evolved by selective breeding, it could be rapidly evolved by radiation treatment, or it could be artificially created via genetic modification. In the end it’s the same outcome.

GMOs:

Even if we choose never to engage in wild species artificial modification, species will grab genes from each other via that natural process of adaptive introgression I mentioned earlier. Which means, shortly, genetically natural species will become a rarity.

Conservation Techniques:

There are so many potentially huge applications of genetic interventions to conservation efforts. Eradicating mice on islands without using poison thereby saving endangered species whose only defense against predators was to be on predator-free islands. Eradicating invasive species. Helping tropical birds survive introduced diseases. Helping American Chestnut against chestnut blight, and hemlock survive wooly adelgid. Helping bats survive white-nose and amphibians survive chytrid. Helping coral survive rapid climate change. Cleaning up pollution and decreasing carbon in the atmosphere. Replacing omega-3 and limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) sources. De-extinction.

Nature is a Spectrum:

Natural has always been a hazy combination of the environmental pressure and the organism in question. A mouse in a house is going to have unnatural behaviors and unnatural genetics. A mouse that has been heavily modified is more “unnatural” though it may be identical (cloned!) to a natural mouse. A completely engineered creature can eventually become natural given enough time to evolve its own way. Natural is not “here” or “not here.” It is about the combination of factors, about the degree of input from humans, about the self will of processes outside our hands. Neither is something is “natural” as soon as we let it go. The history of its shaping matters. Even the wild Condor, carefully raised to be as wild as possible, is not completely natural for generations. The influence of humans takes a long time to erase itself.

This is why it is fine to genetically edit species: their naturalness is not utterly destroyed forever. It is also why we must be mindful: we are eroding naturalness with every step.

Plants growing under an artificial sun.

Feral: Rewilding the Land, the Sea, and Human Life

By George Monbiot

Wilderness is Dangerous

Truly Wild means recreating the before times. It’s untamed, large, and beautiful: cheetahs, elephants, camels, giant sloths, wolves, bison, roaming the land with us. Elephants, wolves, and lions are missing from europe. Cheetahs, camels, and giant ground sloths are missing from North America. These creatures were there before, the land is adapted to them, and it is the blink of an eye geologically they have been missing. It is only our bias towards a sterile, tame nature that leads us to turn a blind eye to the reality that a natural world would be much more, well, Wild.

English Environmentalism

It also covered the crazy politicking of English environmentalism, which apparently is swept up in a craze of sheep pastures as bastions of true wilderness and biodiversity. It was hard for me to take seriously that this is a real position, but I suppose in denuded England there isn’t much wilderness to protect and so it gets conflated with historic preservation. It was all new to me, but provided a helpful model of the kinds of mental sleight-of-hand I must be alert for in environmentalism everywhere. The audio book was enchanting to listen to, often describing beautiful scenery and encounters with nature.

Real wilderness means encountering predators on your way to work.

Whole Earth Discipline: An Ecopragmatist Manifesto

By Stewart Brand

| Environmentalism often turns against technology and progress, falsely claiming it is dangerous. This has led to opposing Golden Rice on flimsy unscientific grounds and thereby causing the needless suffering and malnutrition of nations. It has also lead to opposing nuclear energy, which would have provided much safer, cleaner energy. We hurt our own causes when we commit to unfounded causes in the name of the environment. GMOs and nuclear are powerful allies of environmentalism. |  We picked our poison. |

Where the Wild Things Were: Life, Death, and Ecological Wreckage in a Land of Vanishing Predators

By William Stolzenburg

| Predators perform crucial, humanitarian roles in ecosystems. Removing large carnivores quickly leads to similar outcomes with mesopredator release. Islands with only herbivores are not edens, but hellholes full of suffering. There are lots of fascintating stories and examples of the roles predators play in ecosystems. |  Cute murderers. |

The Skeptical Environmentalist: Measuring the Real State of the World

By Bjørn Lomborg

Alarmism Debunked

A lot of stats showing reported dangers are overblown, alarmism doesn’t hold water, everything is fine and always was. From fears about —

- the finite resources of oil (which have only grown in availability, despite increasing demand),

- finite resources of metals (the same trend),

- food (outpacing population, cheaper than ever),

- population (peaked in rich countries and poor countries are following suit),

- life expectancy (continues to improve),

- water (desalinization has rarely been needed),

- garbage (never blanketed the world),

- nuclear waste (is laughably small),

- topsoil loss (has shown no net loss),

- overfishing (is a product of tragedy of the commons and can be solved, also fish farming has improved),

- tropical forests (… this book is a little outdated),

- oxygen (does not depend on forests),

- biodiversity (will decline 0.7 percent in 50 years),

- forests (only 5% of current tree growth produces all all our paper and wood demand),

- fires (are often areas which have already been burnt and are over reported),

- energy (Bjørn postulated that renewables would be plentiful, and they are now are cheaper than coal and gas),

- and a plethora of other topics such as eutrophication, oil spills, cancer, pesticides, estrogen, gmos, global warming, and more.

Mostly this is a plea for accuracy in reporting, and proportional concern.

There was a time we were afraid the landfills would fill up and the planet would be covered in litter.

What’s so Good About Biodiversity?: A Call for Better Reasoning about Nature’s Value

By Donald S. Maier

I wrote a HUGE overview of all its points.

I read one chapter that explains how biodiversity does not provide resilience or ecosystem services but it seems to cover a LOT of ground with a discerning eye for truth. I plan to read it soon™.

Update: I did read it! And it was very good.

Why do we care about nature?

Wild By Design: The Rise of Ecological Restoration

By Laura Martin

Published in 2022. I haven’t read it yet but I’m looking forward to it!

Transplanting rare plants to ‘protect nature.’